The artist focused almost exclusively on a single subject—the female nude. Depicting a handful of models again and again, Maillol used the female form as means to explore the way mass, volume, line and contour occupy space. Influenced by classical art, his work evokes serenity and harmony and his approach to the human form reflected a new perspective in modern sculpture.

In his mature work, Maillol rejected the highly emotional sculpture of his contemporary Auguste Rodin, preferring to preserve and purify the sculptural tradition of Classical Greece and Rome. “The Mediterranean” (c. 1901) and “Night” (1902) show the emotional restraint, clear composition and serene surfaces which Maillol employed in his sculpture for the duration of his life. Most of his work depicts the mature female form, which he attempted to instill with symbolic significance. He wanted to remove literary and psychological references from his sculptures; resulting in generalized figures which emphasize form itself.

Many of Maillol’s earliest figures are clothed, but after his marriage to his wife Clotilde Narcisse, she served as his principal model, and he began focusing on unveiling the female body. Maillol worked deliberately, creating sketch after sketch, study after study to develop his unique style. He gradually explored different poses—standing, seated, crouching, reclining—in hopes of simplifying and harmonizing the female nude.

By 1905, Maillol began receiving commissions and working on large sculptural projects in stone. He executed a number of monuments and purified the female form; sometimes doubling as a symbolic or allegorical figure. Maillol’s sculptures are silently seductive, reflecting intimate simplicity which is felt throughout his work. Maillol’s work captures the true essence of the female form: silent beauty.

The simple lines and understated form of Maillol’s full-bodied nudes reaffirm the Graeco-Roman tradition of sculpture. In contrast to Rodin, whose expressive sculptures have surface materiality which underscore the process of the medium; Maillol’s surfaces are smooth overall, and his cast bronze sculptures imitate the polished surface of finely finished marble. Rodin had a reputation as the sculptor who had rejuvenated the medium of sculpture from its academic torpor; he was nevertheless one of Maillol’s most ardent admirers. “Maillol”, Rodin declared, “is one of the world’s greatest sculptors…His taste is impeccable, and he reveals a great knowledge of life in simplicity…The most admirable thing about Maillol, the eternal aspect, if I may express it thus, is his purity, his clarity, the limpid character of his craft and his thought” (quoted by Octave Mirbeau in W. George, Aristide Maillol, Greenwich, Connecticut).

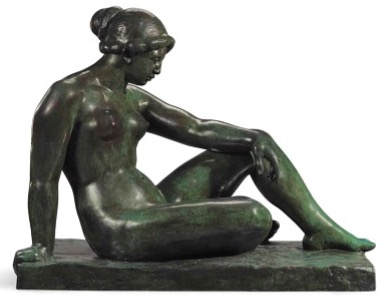

This meditative female subject is the embodiment of Maillol’s mature sculptural vision. Maillol inaugurated the distinct line of a seated, crouching and recumbent life-size nude for which he became famous. When first shown, viewers immediately recognized that “La Méditerranée” was influenced by Rodin. In contrast to Rodin, Maillol offered a serene, unforced, disarmingly direct and casually lifelike manner.

During the German publisher and collector Count Harry Kessler’s first visit to Maillol’s Marly-le-Roi studio in August 1904, he purchased one of his sculptures, an early idea for “La Méditerranée,” which Maillol created around 1900. Kessler asked the sculptor to create a larger version in stone, to which Maillol agreed. The plaster that Maillol presented in June 1905 to Kessler, and later at the Salon, is the second and final version of this subject. This differs from the (present) first version in which the woman’s right arm is bent upwards to meet the upper side of her head, and her right knee raised higher to support her elbow.

Some critics deemed the plaster of “La Méditerranée” at the 1905 Salon d’Automne to be a poor imitation of ancient Greek sculpture. André Gide, however, declared, “She is lovely; she doesn’t signify a thing. She is a silent work of art. One has to go far

back in time, I believe, to find such a complete indifference to any concern foreign to the simple presentation of beauty” (quoted in B. Lorquin).

Maillol intended that this female figure evoke the spirit of his native region around Banyuls-sur-Mer on the Mediterranean coast. While the title today usually includes the French feminine article, Maillol preferred to leave it off. He explained, “I baptized it ‘Mediterranean’… not ‘The Mediterranean’, that is, the sea… This was not the idea I was searching for… My idea was to create a figure, young, pure, luminous, and noble… But isn’t all that the ‘Mediterranean’ spirit? That’s why I chose her name.”

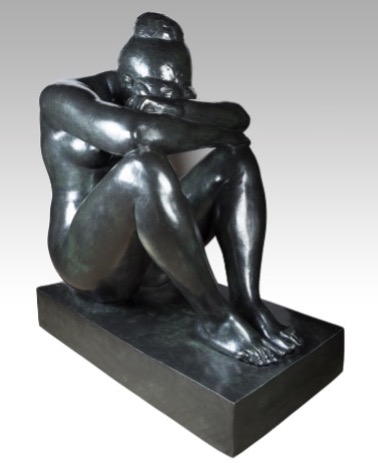

“La Nuit, Première État” is among the best-known and most widely admired of Maillol’s monumental sculptures. It is one of his earliest larger-than-life figures, and it retains the intimacy and simplicity of expression that collectors have long prized in Maillol’s smaller tabletop sculptures. The figure is an allegorical conception in which the sculptor has expressed in a posture of rest and repose. Maillol chose not to identify night with unconscious sleep. Instead, he suggested a temporary state in which the figure has simply desisted from activity and entered a passive period of rest. There is also an emotional dimension which varies from Maillol’s other sculptures; the repose carries a suggestion of weariness, tinged with introspection and melancholy.

Maillol was primarily concerned with a classical purity of line and form which is evident in “Flora” (1911), where the figure’s graceful pose, emotional tranquility and translucent drapery recall ancient statuary. Typical of Maillol’s idealized female figures, “Flora” fuses the serenity and monumental presence of the classical tradition with the immediacy and vitality of a naturalistic depiction. By balancing real, human characteristics with eternal, idealized forms, Maillol dynamically reinvented the classical tradition with a modern sensibility.

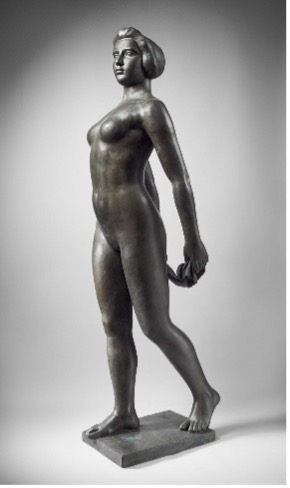

One of Maillol’s most iconic sculpture, “Ile-de-France” was also one of the artist’s longest projects, appearing in various guises and incarnations over fifteen years. Originally conceived in 1910, the work languished in its limbless state until the 1920s. The initial concept was that of a woman walking through water; this effect was to be achieved by not showing the woman’s feet. A later marble version without feet was completed in 1933 and is now in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. However, in the bronze version, Maillol abandoned the idea. The idea of water seems to have been a reflection of the sculpture’s function as a personalization of the Ile-de-France region. Normally, Maillol explored a more abstract sense of the female sublime; this overt interpretation of the region’s personality was eschewed for a more discreet personification, giving the Ile-de-France feet. This new version of the Ile-de- France, finalized in 1925, was much more in keeping with Maillol’s oeuvre. His sculptures explored female perfection and, through that recurring theme, were a celebration of life itself. They are not cold, distant figures, but instead refined, sensuous visions from nature. “Ile-de-France” represents a confident woman. Although she is less curvaceous than many of Maillol’s other subjects, the figure retains his refined form and a timeless image of female splendor.

“La Montagne (The Mountain)” marks the culmination of Maillol’s allegorical renditions of the seated female nude. The sheer size of this figure was a powerful aesthetic statement in these final years of Maillol’s life and instigated his production of other impressive monumental sculptures. Maillol’s model for this sculpture was a young Russian woman named Dina Vierny, whose voluptuous physique bore a striking resemblance to the figures of Maillol’s sculptures. Vierny began working with the artist in 1935, and “La Montagne” was one of the first major works modeled after her image. Maillol rendered several preliminary sketches and four different studies for this sculpture, and ultimately arrived at the final composition in 1936.

In 1936, the Musée National d’Art Moderne commissioned the first monumental version of La Montagne in stone. Maillol began working on the plaster for this sculpture in 1936 in the large studio of his friend, Kees van Dongen, whose brother Jean assisted him on his casting and stone carving. In Brassaï’s remembrance of that day, he told of how the sculpture nearly collapsed and how Maillol succeeded in stabilizing his massive composition: “the weight of the material has caused La Montagne’s left shoulder to begin to slip… Probably the iron armature has given way. Maillol is beside himself, and so is everyone else. Can the disaster be prevented; Van Dongen fetches some planks to shore up the weakened shoulder, while the sculptor tries to strengthen, and all is corrected.”

This monumental nude is seen almost floating in space. The woman is cast out of lead, and the smooth, grayish-blue surface enhances the form’s light and buoyant appearance. Perched delicately on her right hip, the figure extends her legs and left arm create a strong horizontal which is echoed in the plinth beneath her. Resting on her center of gravity, the figure teeters between immobility and movement, suspension and flight. The nude’s face and figure are idealized rather than a portrait of an individual: a personification of air.

In 1938, the city of Toulouse in Southern France commissioned Maillol to commemorate the pilots of the pioneering airmail service, l’Aéropostale, who had been killed in the line of duty. “L’Air (Hand Up)” was cast from a plaster model, and its form was initially inspired by a small terra cotta sculpture Maillol had made several decades earlier depicting a reclining figure resting on wind-blown drapery.

Having grown up in an ancient Greek settlement as well as being a fervent admirer of the Impressionists, Maillol’s sculptures were inspired by the elegance of Gauguin’s Tahitian women as well as the austere and dramatic sculptures of antiquity. Therefore, resulting in works which appear both monumental and intimate. Originally intended as a war memorial for the poet-turned-pacifist Henri Barbusse, Maillol began to work on a sculpture depicting a woman falling to the ground after being stabbed in the back. Due to the financial difficulties in Barbusse’s estate, this version was never completed. Despite the sudden lack of funds, Maillol continued production of the sculpture with a revised theme of the female figure as the personification of “La Rivière”.

In the original context as a commission for a war memorial, the figure appears to take no action against her attack, complementing Barbusse’s own pacifist philosophy. In her revised context as the personification of “La Rivière”, the dynamic twisting of the torso conveys a sense of being swept away by the currents, her arms held up in an attempt to lessen the impact of the waves. The contorted position of her body closely resembles that of the Sabine woman from Giambologna’s famous sculpted group “The Rape of the Sabine Women” (1583) in Florence.

This impressive bronze was created by Maillol at the end of his career, nearly forty years after his first foray into sculpting. Using his longtime muse Dina Vierny as the model for this work, this faultless execution of simple lines and strong, voluptuous proportions is balanced beautifully, making it one of the most successful and well-received works of Maillol’s long career.

Article Edited by Willoughby Thom