In the beginning of the 20th century, artists were continuously trying to find a new way to express the changing times. Impressionists pushed back against realism, but this still wasn’t enough for artists like Paul Cézanne, Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. These artists embodied Neo-Impressionism: an extension of optical concerns with a scientific interest in color. They focused on expressionistic techniques while representing forms in a symbolic manner. There was a sort of complexity of style, while remaining relatively traditional in form. Neo-Impressionism examined the modern condition, and this is something very relevant in our present-day society.

In 1886, Gauguin left Paris to move to Brittany in search of their “exotic” culture. Looking at Paul Gauguin’s life, it’s comedic to think he believed he would find an exotic culture in western France since he found it Tahiti five years later, but many artists believed that due to Brittany’s Celtic origins and distance from a bourgeois society it would be a purely exotic place. Nevertheless, he immersed himself in the local community, further developing his visual language.

Gauguin was in search of a rural utopia in the small town of Pont-Aven in Brittany. It was a remote and unspoiled place with dream-like characteristics, resulting in his expressive, colorful almost surrealist depictions of small-town life. One of his most famous representations of this sensuality was “Vision After the Sermon” (1888). Here, the bright colors, distorted proportions and symbolic representation presents a scene which doesn’t seem real, yet it was real to Gauguin.

Vision After the Sermon (1888)

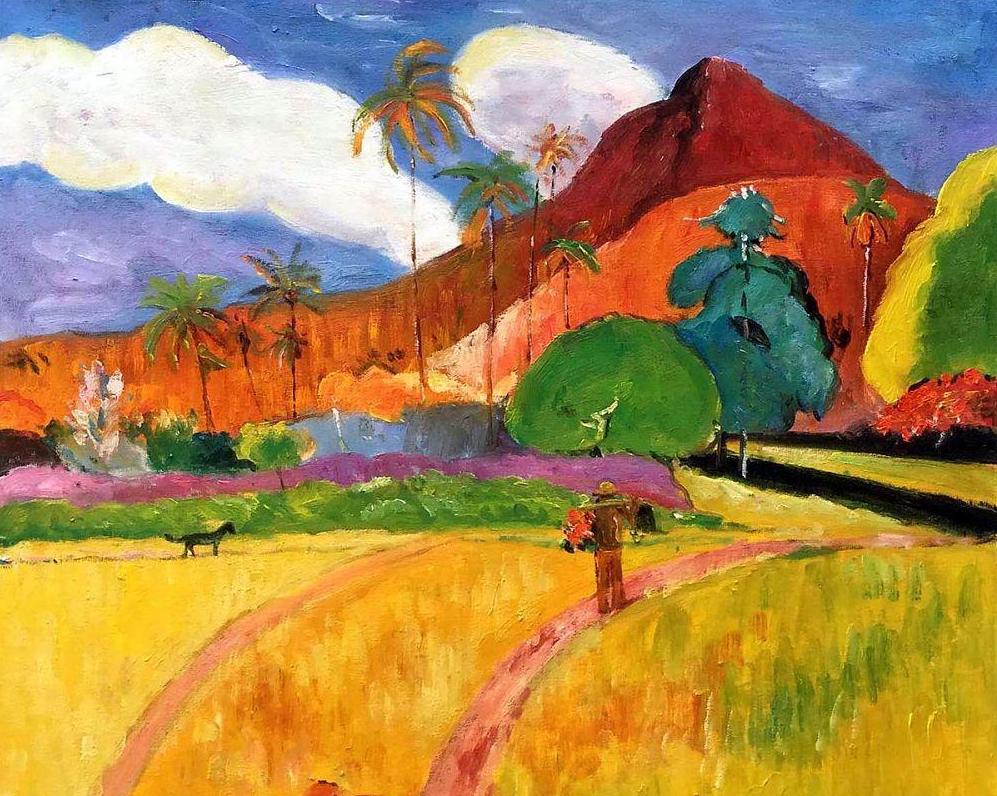

However, even though “Vision After the Sermon” (1888) presents an early form of his use of symbolism, “The Swineherd” (1888) at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California on special loan from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), represents the artist’s foundational work within the realm of Neo-Impressionism. Here, there is an obvious reaction towards the Impressionists which came before him, but rather than loose brushstrokes, color blocking is evident. The natural environment is defined by a vivid division of colors, but it still resembles a developmental stage in Gauguin’s work which is clearly seen in comparison to his landscapes in Tahiti — compare “The Swineherd” (1888) to “Tahitian Landscape” (1891).

The Swineherd (1888)

Tahitian Landscape (1891)

Article by Willoughby Thom