John William Waterhouse (1849 – 1917) was a prominent English painter known for working in the Pre-Raphaelite style, which is characterized by a highly romantic, academic style. The Pre-Raphaelites were a secret society of young artists founded in London in 1848, and the brotherhood’s style was an opposition against the Royal Academy’s promotion of the ideal represented and promotion of Raphael. Nonetheless, Waterhouse, and many of his contemporaries, were known for depicting young, mythical women from ancient Greek mythology and Arthurian legends.

Waterhouse was born in Rome in 1849 to English parents who were both painters. In the 1850s they moved to London where he later enrolled in the Royal Academy of Art. Prior to entering school, he assisted his father in his studio where he explored classical themes which greatly influenced his future work.

At the Royal Academy of Art, he initially intended to pursue sculpture but switched to painting in 1874. He exhibited at their annual summer exhibitions displaying his shared interest with the Pre-Raphaelites in literary subjects—scenes from Lord Tennyson, John Keats, and William Shakespeare—as well as Impressionistic tendencies in the way he exemplified loose brush strokes.

He married Esther Kenworthy, the daughter of an Arts School master from Ealing, and throughout the rest of his life he produced painting in his virtually unchanging style until his death in 1915. Sadly, due to the new trends within modern art during the turn of the 20th century, his style went out of vogue but became a great subject of interest in the late 20th century.

One of the largest John William Waterhouse’s collections is the Tate Modern in London, and the Royal Academy of Art organized a major retrospective in 2009.

“The Lady of Shalott” (1888) Oil on Canvas — The Tate Modern

The Lady of Shalott (1888) is an interpretation of Alfred Tennyson’s poem “The Lady of Shalott,” written 50 years before the creation of this painting. Tennyson’s poem recounts a story of a woman who was suffering from an unknown curse, and she was isolated in a tower on an island called Shalott on a river which flows from King Arthur’s castle at Camelot. Due to her isolation and curse, she was only allowed to look at reality through a mirror, and when this mirror cracked due to Lancelot’s dashing physique, her curse returned. As a result, she was set adrift downstream singing before she met her death.

It’s a tragic story, But Waterhouse only takes a one scene. In The Lady of Shalott (1888), the woman is seen with the boat’s chains wrapped around her hand just before she lets go to float down the river. Her gaze appears to be looking off to the right of the boat as if she is hesitant to let go, but it’s said that she is glancing down toward the crucifix near the candles at the helm of the boat, prior to setting adrift. The beautiful woman’s mouth is agape as if she is beginning her sad song.

The painting has a great sense of balance of light and color despite the number of weeds and items which clutter the scene. The woman is in the spotlight with her glowing red hair, heavenly white dress, and bright face surrounded by dark colors of death and decay. Her atmosphere appears to be blurry while she is set in hyper-realism—Waterhouse has perfected this technique to focus the viewers onto the subject rather than be consumed by her dreary environment.

“Ophelia” (1889) Oil on Canvas — Private Collection USA

This beautiful painting is a depiction of William Shakespeare’s Ophelia, the potential love interest in “Hamlet.” In the play, Ophelia goes mad after the death of her father and suffers an untimely death herself: falling from a snapped willow branch, she drowns in a brook. It’s a tragic tale indeed, but the beautiful Ophelia was a favorite subject for many nineteenth century artists like John Everett Millais, Arthur Hughes, and, of course, John William Waterhouse. Waterhouse loved depicting Ophelia just before death, but to the casual viewer, it would appear as if she was just taking a rest in nature.

Here, in Ophelia (1889), Waterhouse places the dying Ophelia lying in a meadow with a bouquet of freshly picked wildflowers clenched in her hand. In Ophelia’s last scene, she hands out flowers and sings before she goes crazy, which this painting is likely in reference to. The stream which she ends up drowning in is visible in the background.

The colors are perfectly balanced with the varying shades of green which surround the sublimely lovely figure, draped in a heavenly white with pops of purple and yellow of the flowers by her side. To most, it doesn’t appear as if she had just fallen from a willow, but her icy gaze and hand above her head suggest a state of anguish or pain. Waterhouse was deeply interested in rending he owns interpretations of literary and mythological figures and wanted to emphasize her beauty.

This piece was the painting that Waterhouse submitted to the Royal Academy of Art in order to graduate.

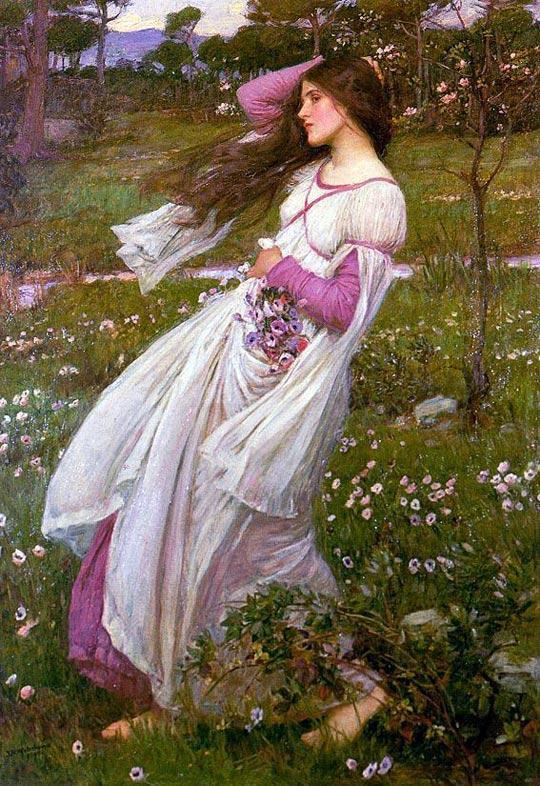

“Windflowers” (1902) Oil on Canvas — Private Collection USA

In Waterhouse’s later pieces, he began to stray away from mythology and focus on nature’s interactions with his beautiful figures. There have been some suggestions that this piece is a representation of the myth of Proserpina because of the spring flowers when she was swept away, but there is little evidence to support this theory. Waterhouse became fascinated with the concept and impact of wind in a scene, this can be compared to the way in which Impressionists would study the conditions of light. Nevertheless, Windflowers (1902) captures Waterhouse’s signature wind featured in many of his paintings.

In this piece, Waterhouse depicts a young, slim model oozing with youthful and charming innocence. She resembles a traditional fair-skinned maiden in classic dressings being swept away by the wind in the English countryside. The girl is enveloped by incredible greenery dotted with little white flowers and bustling trees.

Windflowers (1902) exhibits another wonderful balance of color. The muse’s layers of clothing are deliberately revealed and overlayed as well as made out of the same tones as the flowers that she picks: whites, pinks, violets. Behind the young lady is a small path that appears to have been made by her as she traveled down the hill. In the background, you can see the rolling green hills that the wind gently swoops over which Waterhouse subtlety fades out to view to put the figure into greater focus.

Even though the young, anonymous maiden is said to be the focus of the piece, the wind, in fact, is in the limelight. The wind is at the heart of this work because it directly interacts with everything in focus—her flowing hair and clothing as well as the flowers and the grass—and it is the factor which creates dimension and dynamism within the two-dimensional sphere of the canvas.

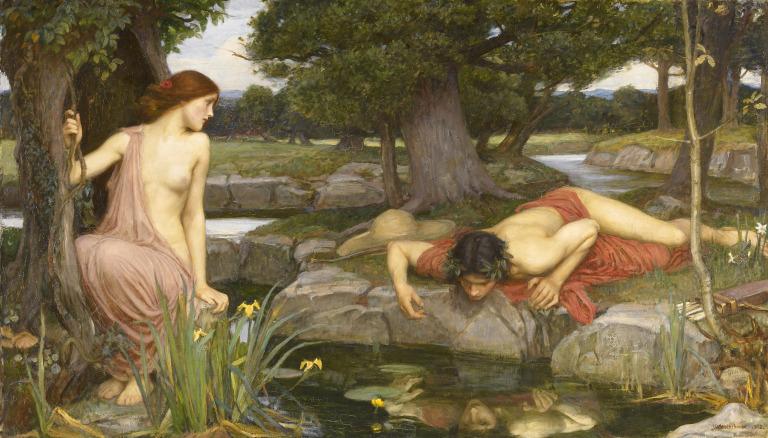

“Echo and Narcissus” (1903) Oil on Canvas — Walker Art Gallery

In Echo and Narcissus (1903), a late work by Waterhouse, is a return to mythology with an interpretation of the Roman myth from the poet Ovid’s Metamorphosis. In the tale, Narcissus falls in love with his own reflection while Echo becomes mute as she watches from afar in pure despair.

Waterhouse, in his typical Victorian style, interprets the myth in his own romantic stylization through the use of beautiful, perfect figures, soft colors, intense realism, and tasteful nudity. He perfectly captures Narcissus’s self-absorption by having him sprawled on the ground eagerly peering into the pond, as Echo sits apart from him on the opposite side of the river. The muted tone of their surroundings creates an ominous atmosphere; it’s almost as if their environment is too manicured due it its highly decorative quality and distinct shapes.

Article by Willoughby Thom